Delivering-Lasting-Value

Organizations can boost profitability by using the customer value hierarchy to identify – and satisfy – customer needs and desires.

What do Michelin tires and London Life’s “Freedom 55” insurance plan have in common? Both products have been the subject of highly successful advertising campaigns over the past decade. The reason for their appeal? Both campaigns focus on desired end states for consumers who purchase those products. In the case of the Michelin ad – which features a captivating shot of a baby sitting in the middle of a tire – the end-state is the promise of safety for the whole family; in the Freedom 55 campaign, it’s the realization of a comfortable, fulfilling retirement at a relatively young age. Who wouldn’t be attracted to products, like these, that promote goals and values near and dear to many a consumer?

Customers want to buy these products not because of their features, but rather, because of the results – or end-states – they will bring.

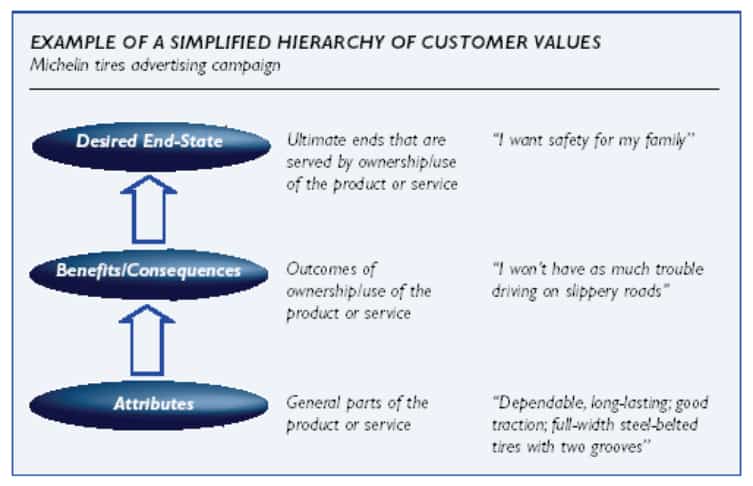

The way in which products relate to customers can be represented as a hierarchy consisting of three levels: attributes, consequences, and desired end-states. In focusing on end-states, companies like Michelin and London Life are appealing to the highest level in what is known as the customer value hierarchy.

The higher, the better

At the lowest, most-concrete level, the customer defi nes the product in terms of its attributes: what the product or service offers (e.g., its features and component parts). All too often, companies define what they do by focusing on the attributes of their product or service – full-width steel-belted tire with straight circumferential grooves – failing to appeal to the upper levels of the value hierarchy, those on which consumers base their buying decisions.

The middle level of the hierarchy is “consequences” – customers’ more- subjective considerations of the consequences, both positive and negative, that result from use of the product. Again, using the Michelin example, customers might describe the consequences of the tire’s attributes as: “The tread design gives them good traction, and keeps me from sliding on slippery roads.” In other words, consequences help companies understand why customers prefer certain attributes.

Organizations can boost profitability by using the customer value hierarchy to identify – and satisfy – customer needs and desires.

What do Michelin tires and London Life’s “Freedom 55” insurance plan have in common? Both products have been the subject of highly successful advertising campaigns over the past decade. The reason for their appeal? Both campaigns focus on desired end states for consumers who purchase those products. In the case of the Michelin ad – which features a captivating shot of a baby sitting in the middle of a tire – the end-state is the promise of safety for the whole family; in the Freedom 55 campaign, it’s the realization of a comfortable, fulfi lling retirement at a relatively young age. Who wouldn’t be attracted to products, like these, that promote goals and values near and dear to many a consumer?

Customers want to buy these products not because of their features, but rather, because of the results – or end-states – they will bring.

The way in which products relate to customers can be represented as a hierarchy consisting of three levels: attributes, consequences, and desired end-states. In focusing on end-states, companies like Michelin and London Life are appealing to the highest level in what is known as the customer value hierarchy.

The higher, the better

At the lowest, most-concrete level, the customer defi nes the product in terms of its attributes: what the product or service offers (e.g., its features and component parts). All too often, companies define what they do by focusing on the attributes of their product or service – full-width steel-belted tire with straight circumferential grooves – failing to appeal to the upper levels of the value hierarchy, those on which consumers base their buying decisions.

The middle level of the hierarchy is “consequences” – customers’ more- subjective considerations of the consequences, both positive and negative, that result from use of the product. Again, using the Michelin example, customers might describe the consequences of the tire’s attributes as: “The tread design gives them good traction, and keeps me from sliding on slippery roads.” In other words, consequences help companies understand why customers prefer certain attributes.

At the top of the hierarchy, desired end-states defi ne the customer’s core values and goals – the ultimate ends that are served by the product or service. These may include such concepts as safety and peace of mind, as in the Michelin tire; or longevity, in the case of a low-fat food product; or perhaps family unity, as the motivation for purchasing a cottage or boat.

Although it is much more challenging for companies to measure and understand the higher, more abstract levels of the customer value hierarchy, there are many reasons why they should try to do so.

First of all, it helps in the product development process If you understand the desired end-states, then you can respond to customer needs and wants by developing products that are much more innovative and creative.

“It also helps organizations sell more effectively,” says Paul Hunt, president of Pricing Solutions. “It drives home the real fundamental issues that are driving customer decisions, thus enabling the sales force to satisfy real customer needs and sell more.”

Take it from the top

At the highest level of the hierarchy – desired end-state – there is more stability in the customer values, making it easier to deliver lasting value. At the middle level, the consequences that are desired by customers are somewhat less stable than the end-states, while at the lowest level, the attributes available to the customer are continually changing. Witness the number of new products introduced every year, under the guise of different varieties, formulations, sizes, or packaging of existing brands. The upshot of all these incarnations is a moving target that makes measuring value at this level both difficult and ineffectual.

Organizations that operate only at the attribute level are always striving to build a better mousetrap, when customers may not be looking for a mousetrap at all! Many companies make the mistake of starting at this level – building a product and then going in search of customers for it. Just because you build it doesn’t mean they’ll come – ask the erstwhile manufacturers of buggy whips!

Successful organizations start instead at the top of the hierarchy, by determining the end-states that are important to the customer and then working backwards to try to design a bundle of goods or services that delivers on these values.

Focusing on ultimate customer needs and desires not only enhances product development and sales, it also overcomes an excessive reliance on price, explains Hunt. “It’s a way of understanding the customer that minimizes the chances of getting stuck in a pricing mindset.” After all, customers are motivated by price only when there is nothing else that infl uences their buying decision.

No Two Customers are Alike

Corporations who understand value hierarchies will also realize that no two customers’ values will be exactly alike. Take, for example, a situation that arose in the pharmaceutical industry. Historically, pharmaceutical suppliers charged high prices for their products, but threw in perks like free medical equipment and continuing medical education. However, recent cutbacks in health care have changed the buying process, and with it, the desired end-state of customers. Enter professional purchasing managers whose motivation is to cut costs, not pay for add-ons to the drugs; those are no longer valued by the buyer.

Pharmaceutical suppliers were unable to adapt to that new reality because they didn’t understand the customer value hierarchy that was driving it. After working with numerous clients to develop value hierarchies that helped them understand this changing environment, segmenting those customerswho still valued the add-ons from those who did not, the companies were then able to adapt their product offerings and pricing accordingly, and train their sales forces to communicate effectively within these new realities.

Focus on the Future

Although customers are adept at responding to an existing product, they are often unable to envision what that product should look like in the future. They can, however, predict their needs at the consequence level. Therefore, companies who have an understanding of the future consequences for

the customer will be in a good position to deliver value in the long term.

Armed with this information, these companies can be more creative in developing new products or services. They can think “out of the box” in devising innovative solutions focused on desired endstates rather than attributes. Chrysler, for example, took this approach when it set out to design an automobile that would meet the needs of the legions of baby-boomers starting families. The result was a completely new kind of vehicle that would soon prevail over the traditional station wagon. The Minivan now accounts for a commanding 25 per cent of the North American vehicle market.

What’s in it for me?

A company’s ability to understand and measure the customer value hierarchy can have a direct impact on profi tability, for the following reasons:

- Companies who understand the value hierarchy will be better able to compare the merits of alternative products and services, and be able to identify those attributes that will provide the most benefit for the customer.

- Focusing on consequences and desired end-states, rather than attributes, will provide a more stable basis for decision-making, since attributes often change, while values do not.

- The “top-down” approach to defi ning customer needs encourages value added solutions and eliminates excessive reliance on price.

- The upper levels of the hierarchy focus on a future state, while attribute levels focus only on historical or current offerings.

- The upper levels offer more opportunity for signifi cant changes in the product or service, while an attribute focus tends to result in less significant changes.